Sometimes when we read a speech, it’s what’s not in the text that causes us to stop and notice.

Universities Minister Michelle Donelan’s pronouncements on “true social mobility” covered lots of ground – and at first I thought it mainly notable for being 1400 words on fair access and participation that not once mentions the Office for Students, its Director of Fair Access and Participation or the massive access and participation function that he oversees.

That wasn’t the only omission when it comes to the apparently increasingly frosty relationship between the Department for Education (DfE) and the Office for Students (OfS). It is true that OfS’ primary regulatory objectives include supporting all students from all backgrounds to access HE as long as they have the “ability and desire”, and it is notable that mention of OfS is missing.

But access wasn’t the only issue of concern. In the speech she said that since 2004, there had been too much focus on expansion, and not enough on “how many drop out, or how many go on to graduate jobs”. Instead, she said, some have been left with “the debt of an investment that didn’t pay off in any sense”.

How very dare she

This was the “catnip” line that caused the usual sector social media meltdown – but as I said in the aftermath of the publication of the Augar review this time last year, surely not all higher education is valuable? It really can’t be the case that every course at every provider right now is just dandy? We are surely not saying that as long as a student chooses a course, then it must be their fault if that course or the outcomes from it are rubbish?

Much ire gets fired at ministers for creating a market, and then not being happy when the market behaves like a market. For example – a really important way in which OfS fulfils its duties is through the provision of information. But even though course level information on continuation and destinations is readily available on Discover Uni and endlessly remixed by league table providers, students keep making the “wrong” decisions. Similarly, having gone to all the trouble of creating a multi-coloured medal system to rate providers on a complex mix of outcomes like continuation and destinations, students keep choosing to enrol in TEF Bronze providers.

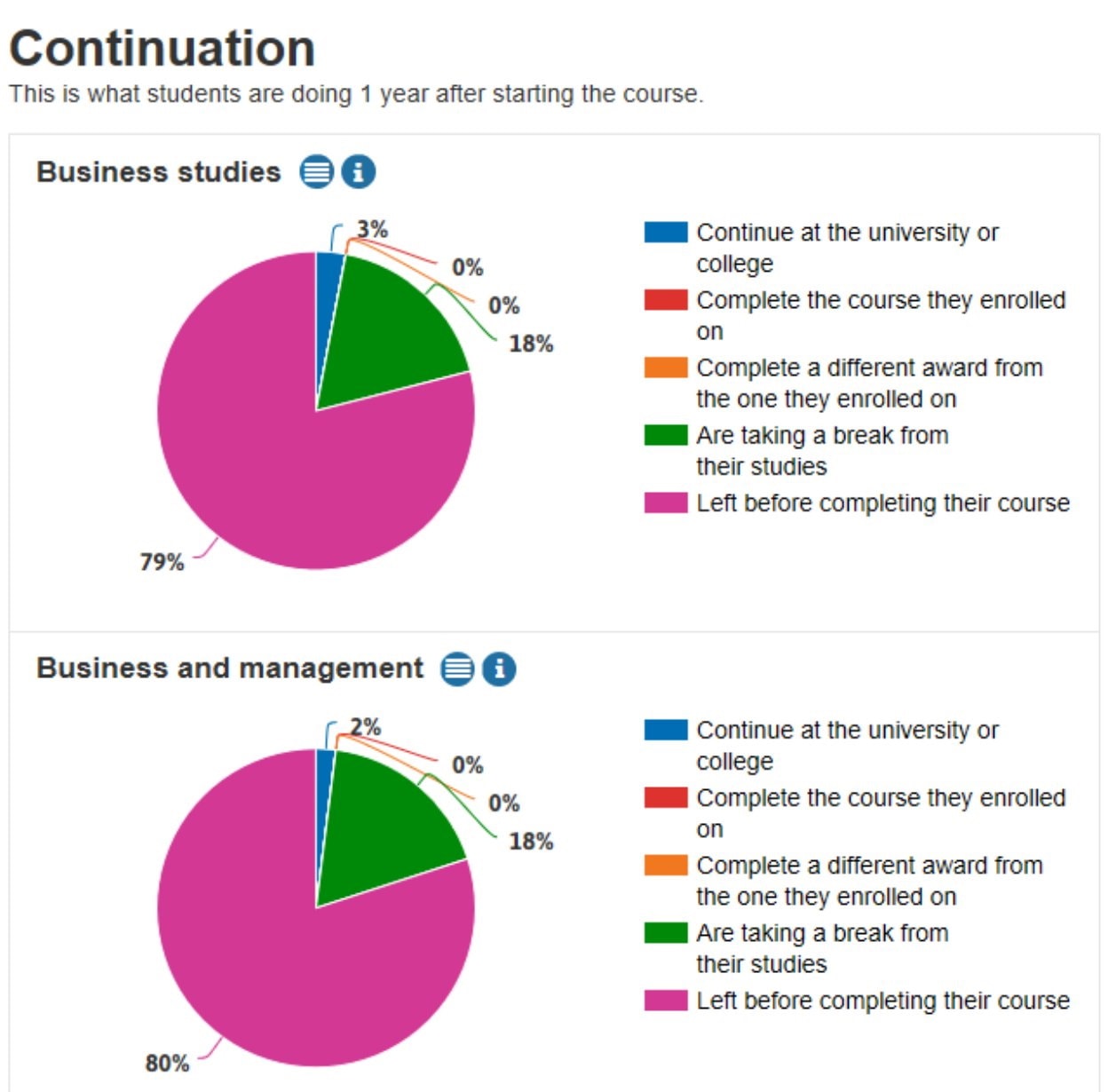

But while there are lots of great reasons to worry about employment and continuation metrics – and endless case studies of valuable student transformation that ticks neither of those neat boxes – sometimes you do look at a set of stats and just think “blimey”. This time last year, for example, in the dying days of Unistats, I was poking about on the site and came across a whole clutch of courses with outcomes like this:

Now let’s set aside that they were from a private provider given access to the loan book by one of Donelan’s predecessors. Are these outcomes low enough for you? If they are, surely Michelle is right. Surely here some students have indeed been “misled by the expansion of popular sounding courses with no real demand from the labour market”, and in the case of courses like this one, these “young people have been taken advantage of – particularly those without a family history of going to university”.

If so, the debate is then where you draw the line, rather than whether the debate over outcomes is legit. And in that case, what we need, perhaps, is a way to help us ensure more of a focus on “how many drop out, or how many go on to graduate jobs”, not less. Who could help with that?

Hello old friend

Into that void re-steps the regulator, whose primary regulatory objectives not only include ensuring that students with “ability and desire” can access higher education, but also include ensuring that those students are “supported to succeed in it”, and are able to “progress into employment or further study”.

A lot of the time OfS is busy running TEF and Unistats to tell students about the aggregate outcomes they might expect to support choice in the “market”. But as we’ve seen, students sometimes need saving from themselves – which means that OfS also makes judgements about what an appropriate minimum level of performance should be on those outcomes.

Several providers trying to get on the OfS register have already failed on these “B3” scores. They’re not benchmarked because “all students, whatever their characteristics, deserve at least the same minimum outcomes”. They work cleverly at characteristics level – OfS’ algorithms take into account different performance by age, (POLAR) quintile, multiple deprivation, ethnicity, disability, sex and domicile. And unlike TEF and Unistats, they look at international students, and postgraduate courses, and even international students on postgraduate courses!

In other words, for all of the gnashing about ministers needing to “show us a course that’s low value”, we already have a system that is regularly and cleverly making quite sophisticated judgments about value – and is setting minimum levels of performance on “how many drop out”, and “how many go on to graduate jobs”. The question is how those judgments might evolve.

Easing the lockdown on OfS consultations

First, we should remember that the current baselines were set at a level that was “more generous” than the policy intention of “ensuring a high quality bar and successful outcomes for all students regardless of their background” might have allowed for – OfS’ own words in here, a document that also announced a consultation on raising them in 2020. You know, now.

Next, we can read from the Donelan speech that to the extent to which OfS has implemented these B3 baselines, Government agrees that they’re currently too low. This shouldn’t be a surprise – although there’s been a General Election and a massive global pandemic since, we shouldn’t forget that Secretary of State Gavin Williamson said last September that there are “unacceptable levels of drop-out rates [and] failures to equip students with qualifications that are recognised and valued by employers” and so “fully supported” OfS’ intention to “revisit the minimum baselines” – imploring it to “consider where current baseline requirements might be raised”.

Who knows whether the rumours about DfE disappointment with OfS are true – in OfS’ defence, initial registration took longer than it intended, and it was mired in legal challenges from providers over those B3 baselines. Indeed the very last thing to happen before lockdown was OfS winning a court case over its application of them when refusing a provider’s application to get on the register.

But now that the pubs are open and the barbers are back, it’s a safe bet to assume that OfS is about to crack on and consult on “raising the baselines so that they are more demanding”. It’s an especially safe bet because OfS used those very words last Christmas, and because Michelle Donelan has hardly hidden her impatience.

What is coming

Some might assume they’ll be able to feed into the coming consultation on whether to use baselines like this at all – but OfS has been to actual court to defend its approach, so good luck with that. Ditto any attempt at introducing benchmarks that account for poor outcomes via student diversity – that ship has long since sailed. There is a debate about how long OfS allows you to run numbers below any baseline in the name of encouraging improvement – but let’s assume that ministerial impatience will now translate into regulatory impatience, regardless of what you put in the consultation boxes.

In truth only three real questions remain. The first is on what we’re counting as a “provider”. Current rules have OfS look at the aggregate performance of a provider in a way that includes franchised provision. But there’s evidence of providers that would previously have failed the baselines when merely validated by Fibchester University that are now in franchise arrangements with Fibchester and hiding their scores in the averages. That’s surely unsustainable.

The second is on the overall level of “minimum performance”. OfS was able to use a bit of reverse engineering to get a result that “looked right” the first time round, but however hard it tries, this kind of metrics-based baseline could inevitably “catch” a couple of high profile, large providers if the baselines go high enough. It somehow has to develop “objective” measures that deliver some student numbers volume without catching a large provider that a Conservative backbencher would complain about – and do it in a way that protects the interests of the students stuck there.

There is a third question. If your way of assuring students (and ministers) that there’s a “minimum” level of outcome performance is to look at averages, it makes no sense at all to take those averages from a provider with 50 students and compare them to a provider with 50,000. And so if you want to avoid collapsing a large provider completely – and you’re keen to tackle what you’ve already called “pockets of weak provision” – you implement those baselines not just at provider level, but at subject or even course level too.

The Donelan speech? Not only have we heard it all before, but it’s just a bit of chivvying. Nature is healing. Like the rest of us, the B3 bear is about to come out of hibernation.

“Similarly, having gone to all the trouble of creating a multi-coloured medal system to rate providers on a complex mix of outcomes like continuation and destinations, students keep choosing to enrol in TEF Bronze providers….”

Like (checks notes) the LSE…